A very belated grade on arguably the most interesting move the Mets made this offseason.

In Early in December, the Mets signed former Yankees reliever Clay Holmes to a three-year, $38 million deal, announcing their intentions to have him transition to the rotation. More than three months later, we’re finally grading that transaction. What gives?

As a peak behind the curtain, sometimes work and life take over, and that definitely played a role in the extended delay here. But the bigger factor was the nature of this signing itself, which prompted a deeper investigation into more generalized questions about the differences between starters and relievers. That effort was not entirely successful, but it did unveil a couple nuggets that can potentially help evaluate the Holmes signing more robustly.

One caveat: We attempt to evaluate these moves with the information that was available at the time of the transaction. That means that Holmes’ strong spring and subsequent elevation to the Opening Day starter spot will not play into our grade. Only the information that was available in December is on the table.

Clay Holmes the reliever is a very good pitcher. Ignore what your Yankee friends told you about his 2024, he still posted a 3.14 ERA while maintaining a 60 stuff rating from PitchingBot, a 124 Stuff+, and 95th percentile stuff in Rob Orr’s metrics. Since being acquired by the Yankees at the deadline in 2021, Holmes has been the fourth most valuable reliever in baseball per Fangraphs, trailing only Emmanual Clase, Ryan Helsley, and Raisel Iglesias. His 66 ERA- over that time ranks 14th, his 65 FIP- 4th, and his K-BB% sits in the top-40 over a 217.2 innings, the 10th most in that time span.

Given that level of talent, the Mets paid a totally reasonable price for a very good reliever; maybe not a contract you want to be routinely giving out, but a fine move for a win-now team. But the Mets are planning to deploy Holmes as a starter, hopping on the recent trend of reliever-to-starter conversions. If it worked for Michael King, Seth Lugo, Reynaldo Lopez, Michael Lorenzen, and (sort of) Jordan Hicks, maybe it can work for Holmes too.

Here’s where we run into the critical question; is Holmes a particularly good candidate for this conversion? We could attempt to lean on the opinion of various smart baseball minds who lauded the signing, but that’s only marginally better than talk-radio commentary in my mind. What we need is some set of metrics that define ideal starter-to-reliever candidates.

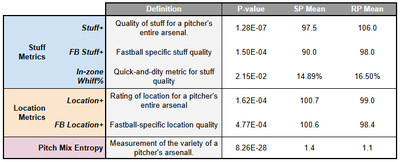

In pursuit of this idea, I attempted to pinpoint some of the quantifiable differences between starters and relievers. Some measurements were obvious candidates to evaluate; stuff metrics (Stuff+, in-zone whiff%), command metrics (Location+, Zone%), data on platoon splits (wOBA differential). Others were more novel; fastball specific metrics (the idea being that a pitcher can’t succeed as a starter without a good fastball) as well as pitch variety, which I captured with a metric I called “Pitch Mix Entropy” (higher with a more varied pitch mix like Seth Lugo, lower for a pitcher who leans on a single pitch like Kenley Jansen). Skip the next paragraph if you’re not interested in the math and go straight to the table below w/ those data that had a significant difference between starters and relievers.

Pitch data for 2024 was downloaded from the MLBAPI using baseballr. Additional data were compiled manually from Fangraphs leaderboards. Pitchers were labeled as either starters or relievers, with those that functioned in both roles left out (an interesting follow-up analysis would be to see where these cross-over guys sit on the spectrum between starting and relieving, but you’d need some precise definitions here that I didn’t bottom out). Each variable was then tested using a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. P-values were corrected using the Benjamin-Hochberg method, w/ effect sizes quantified using the rank-biserial correlation. Pitch Mix Entropy was defined as the Shannon Entropy of a single player’s pitches.

Stuff quality—both overall and for fastballs specifically—sticks out here. The causation is backwards though; lower quality stuff doesn’t indicate a guy should start, starting leads to lower quality stuff. Look to Michael King, who had a 115 Stuff+ in 2022 out of the bullpen, dropped to 105 in 2023 while starting occasionally, and was down to 97 in 2024 as a fulltime starter. Ditto Seth Lugo, who gave back four points of Stuff+ when transitioning to the rotation in 2023. Jordan Hicks went from 119 in 2023 to 103 last year. The interpretation here should be that an ideal conversion candidate has good enough stuff that he can afford to give some back when moving to the rotation.

Command rating has a much more straightforward interpretation; starters unsurprisingly have better grades here than relievers. It’s a fairly standard trope to put wild guys who can’t hit the broad side of a barn in the bullpen, so this isn’t surprising. I’m hesitant to put a ton of weight in this metric, however. Location+ and related metrics are not nearly as sticky as stuff metrics, and the absolute difference is quite small. A simpler metric like zone percentage doesn’t even register as significant. Ultimately, I think there is something real here, but this should likely be regarded as the least critical of our criteria given the associated noise.

Pitch entropy—basically a measure of the variety of a pitch mix—is another clear point of differentiation that makes sense. Only a select few starters succeed without three pitches that are least somewhat reliable, while relievers often succeed with only two or even a single good offering. An ideal conversion candidate would either already have a deep pitch mix, have demonstrated the ability to sustain one in the past, or exhibit more subtle traits that indicate they would be able to add additional offerings. Every notable starter conversion since 2020 except for Reynaldo Lopez has increased their pitch entropy when moving the rotation.

There’s also an obvious fourth factor that we can’t directly quantify; durability. Some guys simply cannot hold up to the load of being a starter, and outside of largely nonsensical scouting truisms about height and shoulder width, we don’t have a lot of public-side knowledge that we can leverage. Suffice it to say that this is a factor to remember, but not one we can account for in a meaningful way.

An interesting extension of this work would be to train a formal classifier (e.g., a random forest) that attempts to identify a pitcher’s role based on some of these metrics. I explored this briefly but not in full, and hope to revisit it in the future when time allows.

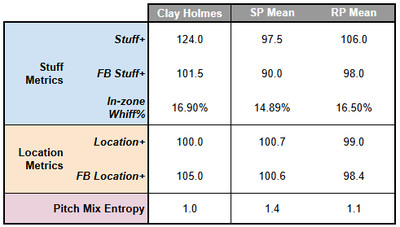

Okay, so we have a couple tentative criteria to deploy. We’re looking for relievers with good stuff, so that they can afford to give some back in the conversion. We want pitchers that have decent enough command to survive as a starter. And we want a diverse pitch mix that will work to keep batters off balance to cover for reduced stuff and multiple looks in the same game. Here’s how Holmes actually rates:

Quite strong overall. Holmes’ incredible stuff certainly passes muster, he’s got more than enough to give back while moving to the rotation. His overall location metrics are right around average, but he locates his fastball very well, something that should allow him to control both his pitch count and walks during longer outings.

As for the variety of his pitch mix, which does check in below average, consider that Holmes threw three pitches more than 20% of the time in 2024; his sinker (56.2%), slider (23.0%), and sweeper (20.5%). If he made a modest adjustment and threw his sinker only 50% of the time and increased the utilization of his breakers to 25% each, his pitch mix entropy would check in at basically average for a starter. That’s a fairly small tweak; starters moving to the bullpen are often asked to double (or more) the usage of their best breaking pitches in order to succeed in shorter bursts. Spreading a ~15% increase across two pitch types should be fairly manageable. Indeed, Holmes’ least effective pitch in 2024 was his sinker, so this is an adjustment he should be considering regardless of what role he’s working in.

This also does not consider Holmes’ ability to add new pitches. Recall that Holmes came up as a starter with the Pirates and has thrown at various times a 4-seam, a cutter, a curveball, and a changeup. Now, none of these pitches were ever particularly effective—the Yankees scrapped them all as soon as the acquired Holmes in 2021—but there’s presumably some level of residual feel here. It’s not a stretch to assume that the Mets can revive one or two of these offerings and further increase the variety of Holmes’ arsenal.

We can’t really answer the durability question (frankly no one can), but every other box is checked here. Holmes has great stuff, adequate command, and a pitch mix that, with relatively minor adjustments, should at least on par with other starters. Depending on just how much stuff bleeds in the conversion and what sort of tweaks the Mets can make to the pitch mix, there’s real upside as a starter here in my eyes.

Back to reality, where I’m writing this article three months late and we’ve watched Holmes dominate all spring. He’s maintained the quality of his previous arsenal components while experimenting with a 4-seam, cutter, and changeup, with the latter proving to be particularly effective. Every sign is pointing in the right direction on this move, to the point where I think Holmes has a shot at Cy Young votes this year.

If that information was in scope, this would be a slam dunk A+. As stated previously though, it’s not; we can only use what we knew in December. From that lens, Holmes is a promising conversion candidate with the right ingredients to work in the rotation and high-end stuff that raises the ceiling significantly. He also has the fallback of being one of the better relievers in baseball if this experiment is unsuccessful. That’s a tidy bit of work even without the knowledge time has gifted us; this signing receives an A.