The Dog is Loose

In the second installment of this three-part interview series, 9 year NBA veteran, The Junkyard Dog himself takes us on a journey into how he became “The Junkyard Dog” as a rookie with the Detroit Pistons.

If you missed part one, be sure to catch up here and stay tuned for part three!

Once the excitement of the NBA draft had commenced, it was time for Williams to make his way to Detroit Rock City along with Ben Wallace as the two newest members of the Detroit Pistons. During those days NBA veterans would claim a rookie as their own, and Williams was claimed by none other than one the most legendary Detroit Pistons bad boys, Rick Mahorn who alongside Grant Long had given Williams his nickname and newfound of The Junkyard Dog. “I had to run errands for him, get doughnuts and things like that- but Rick was 42 years old and was trying to help me have a long career. That was his initial job, and he did it.”

With a new nickname, Williams embarked on a personal journey to fully cultivate his persona as The Junkyard Dog, both on and off the court. He took immense pride in embodying the tenacious and unyielding nature that the name represented, meticulously refining his character through his conduct and demeanor, so much so that it became routine for Williams to startle his teammates during practice or as they exited the locker room with his newly perfected, deep growl—eerily mimicking the sound of a ferocious pit bull, often leading his teammates to believe that a wild dog had somehow gotten loose in the Palace of Auburn Hills.

“I had to develop a bark, and it had to be so realistic that they thought it was a dog.” Williams told of his process to develop his true to life growl, “I would listen to ferocious dogs bark… and I had good representation- DMX was a good barker, Q-Dogs from The Fraternity were great barkers.” Williams explained, “As you listen to different people bark, you develop your own style because there is no right or wrong answer. And then I recruited fans to start barking with me because I was relentless, and I was an opportunist, and I was leveraging everything. So, the fans became that Dogg Pound that I needed, and they were so obliging in every single city. The Dogg Pound just grew every single day, and it still grows to this day.”

In addition to having one of the original “Bad Boys” guide him through the early stages of his NBA journey as a young pup, JYD also had the privilege to play alongside and learn from another NBA great in Grant Hill. “He taught me how to be a true professional franchise player,” Williams recalled one evening with Hill that profoundly impacted his life, as he sought to learn the intricacies of the business behind being a professional athlete from one of the most highly endorsed players of that era.

“I went over to his house for dinner, and he went over every individual endorsement of his, but only because I asked. He taught me that this is what it takes to be THAT!” Williams continued, “When I got traded to Toronto, Vince Carter was the franchise player, but he had conflicting endorsements already with the team sponsors. So, the (Raptors) could not use Vince as the main spokesman for their product partners. (For example) Vince had Gatorade, and the (Raptors) sponsorship was through Coca-Cola. Vince had Nike, and the team had Reebok.” Williams recalled, “When I re-signed (with Toronto), they had a whole presentation making me the spokesman for all their corporate partners. And that’s from being R.O.L.E. When I went out on community engagements with the team I had the same mentality. I wanted to sign every autograph and take every picture with every fan. I wanted to make sure everybody had a good time and were entertained so I interacted with the audience at all times, barking, greeting them, smiling, signing autographs… whatever it took, and that’s what sponsors and partners like. So, guess what, now I’m getting these endorsements, and when people ask me how I did that… R.O.L.E.!”

Before Williams earned his endorsements off the court, there was a time early in his career where things looked bleak, and didn’t quite unfold as he had envisioned. During his rookie season, JYD appeared in just 33 games, primarily coming off the end of the bench to play in garbage time. The frustration of not playing was more challenging for Williams than the battles on the court itself. “The first few games of my career I was on the injured reserve list, and I wasn’t injured.” Williams explained, “When you go on the injured reserve list back then, you had to be on it for five games, which typically could last up to two weeks. When I got out on the court for the first, I was grateful, and I was thankful.”

Being placed on the injured reserve list was a tough pill for Williams to swallow, serving as his first harsh “welcome to the league” lesson—a reality he had to learn the hard way. “(Teams) could not come and ask you to (go on IR). You almost had to volunteer, which meant (the team) had to call your lawyer or your agent. Then your agent had to determine if he was going to talk to you about it. It was a little tricky back in the day.” Had Williams not accepted his agent’s proposal, he faced the genuine risk of being cut from the team. Rather than seeing this as a setback, he recognized it as a crucial opportunity for self-sacrifice to earn his stripes within the organization. By demonstrating his commitment to being a team player, Williams believed he would secure his acceptance amongst his teammates and the organization.

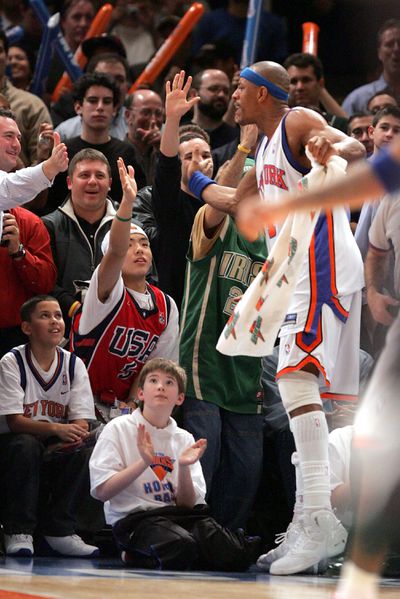

Photo by Doug Pensinger/Getty Images

After garnering the respect of his teammates, coaching staff, and the organization during his rookie season, Williams never looked back. In his sophomore year, his minutes on the court tripled to 16 per game over 77 appearances, including three starts. His field goal percentage surged from .392 to .524, and he recorded three double-doubles all off the bench. On March 2, 1998, he set a new career high with 14 rebounds in just 22 minutes of action during a 100-94 victory over the Dallas Mavericks However, that record didn’t stand for long, as he eclipsed it in 1999, grabbing a career-high 21 rebounds against the Charlotte Hornets. His stats continued to improve year after year, and by 2000, Williams finished fifth in the voting for the NBA’s Sixth Man of the Year award.

Williams took pride in doing the dirty work on defense and controlling the glass, traits that became his hallmark. When asked who the toughest player he ever had to guard was, his answer was surprising. It wasn’t offensive powerhouses like Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, or Shaquille O’Neal, as one might have expected.

Photo credit should read J.P. MOCZULSKI/AFP via Getty Images

“The people that resembled me… Dennis Rodman!” Williams recollected, “The good offensive players were not always the worst to guard. They just always gave you something to focus on as a defender and they were very gifted. You weren’t put in a situation where you need to go out and stop this person. (The coaches) would say to go out and slow this person down, make it harder for them and just by your name alone, you’re going to make it tougher based on your tenacity.” Williams explained, “But the guys who don’t score, the guys who basically got paid to do what I was doing, those were the ones because they’re out there creating energy for their team.”

Having one of the leagues soon to be greatest defenders of all time in Ben Wallace as his partner in crime didn’t hurt either. “We were in the same locker room, and in the same weight room chewing on dog food every day”, Williams joked.

Stay tuned for part three, where we wrap up our interview with The Junkyard Dog. We’ll dive into his close friendship with the late, great Dikembe Mutombo, including their joint efforts to make a difference around the world. We’ll also discuss his time with the New York Knicks and his extensive philanthropic work with today’s youth, including his organization The JYD Project, and his role as the lead spokesman for the “Shooting for Peace” initiative.